I was grateful to be asked onto the recent Scottish Football Forums Podcast by host John Bleasdale. The itinerary asked me to reflect on UEFA EURO 2020 – right up my street! John’s invitation led me to seek a better understanding of what went right and wrong tactically for the Scotland Men’s National Team at their first major tournament since France 98. As most reading this will know, Scotland exited EURO 2020 after the first round, which feels like the Tartan Army’s eternal destiny on the big stage. Nonetheless, we were left with plenty to digest after a summer of top-level international football.

Scotland v Czech Republic, Hampden Park, Glasgow, 14 June 2021

Pre-match

Scotland’s major team news on 14 June 2021 was the loss of Arsenal’s Kieran Tierney to an injury picked up in training on the eve of the Czech Republic match. Positioned at left centre-back in a 3-5-2 formation, Tierney plays a pivotal role in carrying the ball progressively up the pitch for Scotland, creating overload after overload for the opposition when fit and on form.

Playing for Arsenal in season 2020-21, as per StatsBomb data via FBref, Tierney had registered over 1,000 ball carries in the English Premier League, 49 of which were in the final third of the pitch. For Arsenal that season, only talented England international Bukayo Saka registered more final third carries than Tierney with 54. Statistically, over season 2020-21 Tierney was also amongst Arsenal’s top three players for defensive clearances (77) and blocks (50). Without Tierney, Scotland would be weaker offensively, and possibly defensively, although replacement Liam Cooper of Leeds United was solid cover at left centre-back.

Tierney’s injury was not the only shock when the team news filtered through to the nervous Tartan Army. Following the recent emergence of Southampton’s Che Adams as a Scotland international – stylistically an ideal second striker for a 3-5-2 formation – most expected Adams to start alongside main central striker Lyndon Dykes of Queens Park Rangers. Steve Clarke instead opted for Ryan Christie of Celtic (now Bournemouth). Few Scotland fans would have grudged Christie his place after his Nations League heroics a few months earlier, but most would have considered Adams alongside Dykes to be more attacking.

The surprises did not end there. In midfield, many expected either Celtic’s Callum McGregor or Chelsea’s Billy Gilmour, but neither started the match. Instead Manchester United’s Scott Mctominay, more often played at right centre-back for Scotland, started as the midfield pivot, with John McGinn (Aston Villa) and Stuart Armstrong (Southampton) either side of Mctominay in central midfield. After a good season in Belgium on loan from Celtic, Jack Hendry of Oostende (now Club Brugge) was handed Mctominay’s right centre-back role.

There were no surprises at goalkeeper, with Derby County’s David Marshall retaining his spot as number one after his penalty heroics in the Nations League. At left wing-back, as a former English Premier League and Champions League winner, captain Andrew Robertson of Liverpool would carry the weight of expectation on his shoulders. At right wing-back, Motherwell’s Stephen O’Donnell still had a bit to prove to many Scotland fans, possibly due to occasional nervous moments on the ball, and having won all of his caps whilst with Kilmarnock and now Motherwell. To complete the eleven, Grant Hanley of Norwich City had won over most doubters by now in his role as Scotland’s central centre-back stopper.

In order of squad numbers, the Scotland team named to face Czech Republic on 14 June 2021 were in 3-5-2 formation as follows: David Marshall (1); Stephen O’Donnell (2); Andrew Robertson (3); Scott McTominay (4); Grant Hanley (5); John McGinn (7); Lyndon Dykes (9); Ryan Christie (11); Liam Cooper (16); Stuart Armstrong (17); Jack Hendry (24).

In order of squad numbers, the Czech Republic team were in 4-2-3-1 formation as follows: Tomáš Vaclík (1); Ondřej Čelůstka (3); Vladimír Coufal (5); Tomáš Kalas (6); Vladimír Darida (8); Patrik Schick (10); Lukáš Masopust (12); Jakub Jankto (14); Tomáš Souček (15); Jan Bořil (18); Alex Král (21).

First Half

Scotland started the match brightly, and Robertson immediately looked a threat breaking forward on the left. O’Donnell looked nervous on the right however, and goalkeeper Marshall declined offers from Hendry to play the ball short and build from the back. Such slower measured build-up play may have allowed O’Donnell and Hendry to settle into the match, but the experienced Marshall looked slightly frantic in the opening stages, possibly feeling the magnitude of the occasion.

This overly direct play arising from Marshall’s long kick-outs was a pattern throughout the match, and definitely caused Scotland to concede possession far too easily at times. StatsBomb data via FBref states that Marshall attempted 27 long passes against the Czechs, only 9 of which were completed – a poor 33.3% completion rate. Interestingly, Czech goalkeeper Tomáš Vaclik posted similarly poor long passing numbers, with 25 long passes attempted, and only 9 completed – a 36% completion rate. In the light of Vaclik’s wasteful distribution, this was a chance missed for Scotland in the area of ball retention.

Scotland v Czech Republic @ EURO 2020 – Data viz

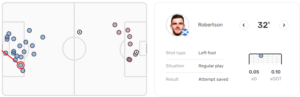

I was fortunate enough to be in Hampden Park that sunny afternoon, one of just 9,847, and I will concede I was far from impartial as I prayed for a winning start to EURO 2020. From the Hampden stands, Robertson’s chance on 32 minutes felt like Scotland’s big moment of the first-half.

The move started with a throw-in on Scotland’s right, taken by O’Donnell towards Dykes, who challenged for the high ball, which broke to Christie, who remained composed, took a great first touch, and weighted a perfect pass to the onrushing Robertson. Scotland’s captain shot first-time, side-footing firmly with his strongly favoured left foot. Unfortunately for Scotland the shot was too straight and too high, and Czech goalkeeper Vaclik tipped the ball over the bar for a corner.

At the time this felt like a huge missed opportunity, as a goal for Robertson at this moment would have decisively announced our arrival back on the international big stage. Surprisingly, Opta data as per Fotmob rated the expected goals (xG) value of this Robertson shot at just 0.05 xG – a 1 in 20 goal chance. Opta’s expected goals on target (xGOT) metric was also applied to this Robertson chance, raising the goal probability to 1 in 10. This felt like a better chance than the underlying numbers suggested, and on reflection I still feel this was one of the most significant moments of EURO 2020 for Scotland, as it set the tone for what lay ahead of us in front of goal.

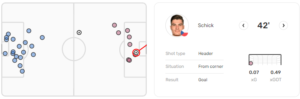

In the 42nd minute disaster then struck for Scotland.

The Czech Republic’s most progressive passage of play of the match so far saw them win three consecutive corners. The third of these corners was initially headed clear by Hanley, but only as far as Vladimír Darida. The Czech captain remained composed, and fed West Ham right back Vladimír Coufal, who had made a late overlapping run on the right wing, which was closed down too late by O’Donnell. Coufal’s terrific right-footed cross was met by a superb header from Bayer Leverkusen striker Patrik Schick, who out jumped Hanley and Cooper, leaving Marshall with no chance. 0-1 to the Czech Republic.

Opta data via Fotmob attributed an xG value of 0.07 to Schick’s headed goal – a 1 in 14 goal scoring chance. A low xG value, and a testament to the quality of the header. This trend would continue for Schick throughout EURO 2020, and he finished the tournament on an impressive 5 goals from chances worth only 2.6 xG.

Half Time

0-1 at half time was definitely not the scoreline Scotland had hoped for, or indeed deserved. In the Hampden open air studio, Darren Fletcher identified O’Donnell as slow to react to the second phase of play at the corner kick which led to Schick’s headed goal.

Renowned football tactics writer Michael Cox recently defined ‘the second phase’ as the point when the initial corner or free kick is cleared, and the opposition immediately regain possession and launch the ball into the box for a second time. Cox goes on to describe the second phase as an awkward phase of play for the defending side, who automatically shift out of their set-piece positions, but often cannot transition into their usual defensive shape in time, so briefly lack proper organisation. Darren Fletcher however was less than sympathetic, expressing a view that Schick’s header was a poor goal for Scotland to lose.

The pundits also evaluated that the Czech Republic’s main aim had been to capitalise on set plays – a game plan they had executed effectively during EURO 2020 qualification. Also, that West Ham midfielder Tomáš Souček had man-marked McGinn in the first half, nullifying McGinn’s attacking threat.

Paul Lambert, a veteran of Scotland’s last major tournament appearance at France 98, evaluated that it was unnecessary to play three centre-backs against one striker, and assessed that one Scotland centre-back must be willing to step into midfield to unsettle the Czech midfield, who he felt were having too easy an afternoon. Lambert felt this would ease the workload of Armstrong and McGinn, who he assessed were being asked to do too much running to cover the wide areas, leading to our wing-backs becoming pinned back too often.

Steve Clarke’s response to the Czech goal was a half time substitution – Che Adams for Ryan Christie. This would be the last we would see of Christie at EURO 2020, probably more for tactical reasons than any other, as his performance on the day had been far from disastrous. On a luckier day Christie may have superbly assisted one of Scotland’s most memorable goals. Had he done so, his tournament may have played out very differently – such are the fine margins of football at the elite level.

Second Half

Scotland were slow to start the second half, and the Czechs attacked Scotland immediately. Marshall was called into action twice in quick succession as Schick then Darida both had shots on target.

Scotland rallied immediately, with Adams making an instant impact, holding the ball up effectively and bringing others into play. A decent move in the 48th minute led to a Robertson cross from the left which forced Czech goalkeeper Vaclík to palm the ball away. O’Donnell collected the loose ball and laid it off to Hendry, whose shot from outside the box struck the Czech crossbar. Opta as per Fotmob attributed an xG value of 0.05 to this opportunity – the same value as Robertson’s earlier chance.

Momentum was now with Scotland again, and Hampden Park, which had been understandably flat since Schick’s 42nd minute goal, felt energised once again. A searching Robertson pass led to a desperate defensive lunge from Tomáš Kalas who deflected the ball upwards and lobbed his own keeper Vaclik. Unfortunately for Scotland, Vaclik reacted brilliantly to claw the ball away ahead of Dykes, who had looked favourite to finish the job and bundle the ball home.

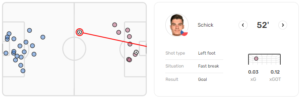

Then came the moment this match will always be remembered for.

With momentum still with Scotland, Hanley went down injured on the halfway line with a knock after 50 minutes, and Robertson ushered the ball out of play so Hanley could receive treatment. Hanley then left the pitch and waited to be signalled to return by referee Daniel Siebert. Play then restarted with Scotland attacking on the left wing. With Hanley still off the pitch, Armstrong played a wayward medium length pass infield which Hendry collected. Hendry then attempted an ambitious shot from 30 yards, declining a simple pass to O’Donnell who was free on the right. Soucek easily read the danger and blocked Hendry’s shot, causing the ball to cannon towards the halfway line, and perfectly into the path of Patrik Schick.

Hanley was now back on the pitch and sprinting towards Schick, but was unable to close him down quickly enough. Schick ran onto the ball unopposed, and in a moment of spectacular technique, connected with the ball first-time with his left foot from just inside Scotland’s half. As a spectator in Hampden, I was behind the trajectory of the ball, which arced several yards out to the left, before curving to the right. With Scotland on the offensive, the unfortunate Marshall had assumed a sweeper keeper position, and was too far outside his penalty box to recover. Schick’s incredible shot had looked like a goal from the second it left his foot, and sure enough it found the target from 54.35 yards (49.7 metres) – the longest goal ever at the EURO, and the UEFA EURO 2020 goal of the tournament. Opta as per Fotmob attributed an xG value of 0.03 to Schick’s wonder strike – a 1 in 33 chance – which seems ridiculously high, given the rare quality of the goal. 0-2 to the Czech Republic, and two goals for Schick.

From a personal point of view, having now overcome the disappointment of Scotland suffering this goal, I can honestly say it was the best goal I have ever witnessed, and I am pleased to have been present for a classic EURO moment.

Scotland played with spirit after the crushing blow of Schick’s wonder goal, and created three good chances inside 5 minutes.

On 62 minutes Dykes had the highest xG value chance of the whole match from close range (0.65 xG), which brought yet another save from Vaclík, after a good cross from Robertson and a header at the back post from Adams had kept the ball alive.

On 64 minutes Armstrong made an excellent progressive run, carrying the ball to the edge of Czech penalty area, before hitting a decent shot. But Kalas blocked yet again to send the ball looping over his own goalkeeper and onto the roof of the net. Cheers broke out from some sections of Hampden who thought Armstrong had scored. Luck was evading Scotland and was with the Czechs.

On 66 minutes Dykes had another big chance after good build up play again involving Adams which led to a cross from Hendry to an unmarked Dykes who shot first time with his left foot from 10 yards out. Unfortunately Vaclik made yet another good save, this time with his right foot. This second Dykes chance was of 0.29 xG value.

At the conclusion of Matchday 1, Lyndon Dykes had the highest xG tally of any player at EURO 2020 (1.12 xG) – but no goals.

In a final roll of the dice Steve Clarke shuffled his pack, introducing substitutes Callum McGregor, Ryan Fraser (Newcastle United), James Forrest (Celtic), and Kevin Nisbet (Hibernian).

Scotland’s best moment following these changes was on 83 minutes. A switch of play from Robertson to replacement right wing-back Forrest led to the Celtic man driving into the Czech box. Forrest’s skilful dribbling saw him beat two men, but yet another last ditch defensive block, this time from Ondřej Čelůstka, snuffed out the danger. Forrest stood with his hands on his head in disbelief, his feelings of despair shared by a whole nation. Chance after chance created for no reward, and a final score of 0-2.

Full Time

In terms of the xG, StatsBomb via FBref rated the match 1.8 xG to 0.9 xG in Scotland’s favour. Similarly, Opta via Fotmob rated the match 1.95 xG to 1.09 xG in Scotland’s favour. The Czech Republic’s two goal victory therefore provided a three goal swing in expected goals probability.

The Czech Republic also did not pass the ball particularly well on the day, completing just 270 of a mere 386 total passes, with an overall team pass accuracy of just 70%. Surprisingly, in a match in which Scotland perhaps underperformed in midfield, Steve Clarke’s men completed 386 of 503 passes, with an overall pass accuracy of 77%. So Scotland also passed the ball considerably better than the Czech Republic on the day, and finished the match on 57% possession to the Czech Republic’s 43%.

In a strange match, ultimately decided by the clinical finishing of Schick, Scotland had the edge in almost every statistical category other than the most important – goals. The England game at Wembley was now crucial if Scotland were to stay alive at UEFA EURO 2020.